Elsewhere is a narrative research project exploring ideas of home, movement, and belonging through lived experience.

This chapter unfolds along the Bangladesh–Monfalcone axis, connecting rural poverty and European industrial peripheries to question how migration is framed, perceived, and managed.

Not to explain or judge, but to observe what emerges when complexity is not simplified.

This entry follows

Part#1: THE CROSSING

Part#2: THE RELATION

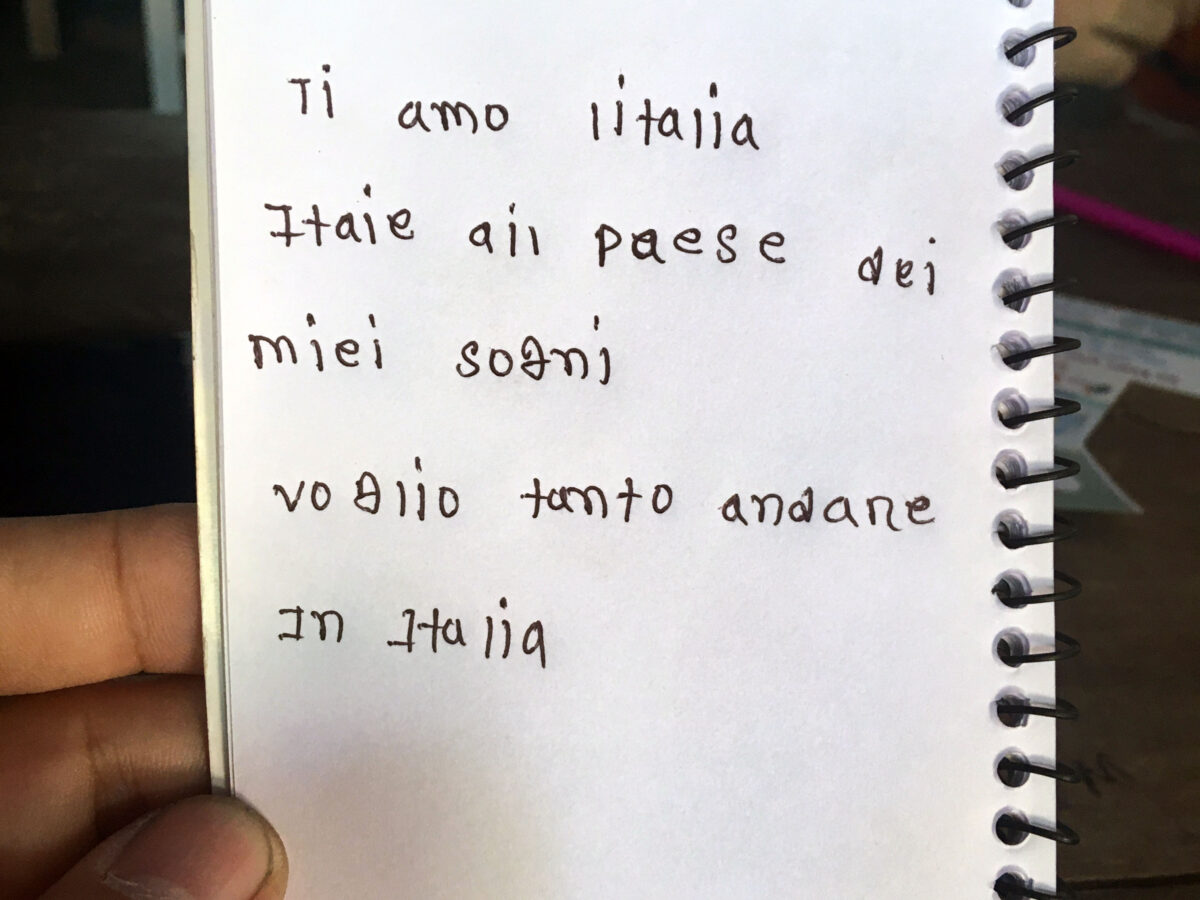

Italy, my dream country!

In Bangladesh, when I meet someone new, I’m always asked where I’m from. When I say Italy, 99% of the times I’m told: “Italy is my dream country!”

Seldom “Europe.” Sometimes simply “abroad.”

It’s not an articulated sentence. It’s a look. A projection.

Italy as a promise of order, work, dignity, a future. An elsewhere where things “work,” where effort is rewarded, where life stops being a daily chase.

Every time I wonder what to answer. Because telling the whole truth at once is unfair. And lying would be too easy.

That dream is born from distance. From what is not seen, or from what is seen in films, advertisements, in the endless stream of glossy nonsense that underpins narratives serving entertainment and consumerism.

It doesn’t see precariousness, loneliness, bureaucracy, distrust. It doesn’t see that here the margin for error is minimal, especially if you are a foreigner. It doesn’t see that the promise of integration often stops at words.

In Monfalcone, I have seen Bangladeshi workers treated less as individuals and more as a category. Nothing essential about the people had shifted, only the ground beneath their feet. And this has a huge social impact.

Dreams are never symmetrical. Those who dream from afar imagine possibilities. Those who receive up close often see only costs, fears, threats.

And in between are people who move not out of ideology, but out of necessity. To send money home. To build something that, in their country of origin, would not be possible.

“One day I will go to Italy,” they would tell me.

I listened, nodded, and thought that no country should be a dream. It should simply be a place where you can live without having to run away from something else.

But as long as the world remains this unequal, dreams will continue to move—aligned with our tendency to look away, to avert our gaze, especially when it comes to connecting cause and effect in what we desire, use, and throw away.

Separate the Plastic, Not the Problem

In Bangladesh, trash is everywhere.

On the streets, in the fields, along paths, near houses. It’s not hidden, not an exception. It’s part of the landscape.

At first it disturbed me a lot. Then I understood that reading it as individual neglect made no sense. It’s not a lack of education. It’s the absence of a system. There is no real waste-collection policy, no widespread education, no viable alternatives. When the priority is eating today, trash is not a priority.

The more educated locals I spoke with know this perfectly well. They say it openly: what’s needed would be a top-down program. But they also know that, right now, politics has other urgencies. Survival comes first.

And this is where the gaze inevitably turns back to us.

In the context I come from, recycling is often framed as personal responsibility.

Separate correctly, feel absolved.

I began to question how much of that responsibility is structural and how much is simply shifted downward: if we separate plastic from paper properly, if we choose the right bin, then we are doing our part. Meanwhile, we keep producing absurd amounts of plastic, we keep basing the economy on fossil fuels, and we shift responsibility onto the individual citizen.

If you recycle badly, it’s your fault.

If you recycle well, you can feel at ease.

But the problem is not where we throw the plastic away. The problem is that we keep producing it as if there were no alternatives. And alternatives do exist—but they are inconvenient for those who profit from the current model.

In some places, waste is impossible to ignore.

In others, it is managed at a distance.

The distance changes perception. Not the problem.

This does not make seeing waste everywhere acceptable. I couldn’t get used to it either. Whenever I found a bin, I put everything in it. It’s a habit I haven’t unlearned. The body reacted before the mind.

Perhaps that’s the point: trash always says something about a society.

About what it considers a priority. About what it is willing to see. And about what it prefers not to look at.

This is not just an environmental issue. It is a political one, even when we pretend it isn’t.

Shifting responsibility onto the citizen through superficial options that don’t solve the problem is just another shade of hypocrisy—necessary to sustain an economic system that does not care about the environment at its roots. Anywhere in the world.

Bangladesh There, Bangladesh Here

There is a Bangladesh I encountered there, and a Bangladesh I see here.

There, in rural villages, being European meant curiosity. A window onto the world. Sometimes even a source of pride. Not because I was someone special, but because I represented a possible elsewhere—something that widened the horizon.

Here, in Italy, often in Monfalcone, being Bangladeshi means something else entirely. It means being seen as a problem. As a presence to manage, contain, explain. Not as a person moving along a trajectory of necessity, work, survival.

What changes is not character. It is context.

Majority and minority are not identities. They are positions.

And positions shape how you are seen.

There, they are the majority. They have little, but they have a context that recognizes them. Here, they are a minority. They have more materially, but far less symbolically. They have much more to lose: their job, their permit, their reputation, their ability to stay.

In Monfalcone, the main industry is ship-building, where Fincantieri employs thousands of foreigner workers, prevalently from Bangladesh. There, I did not see a cultural failure. I saw a political failure spanning twenty or thirty years. A community dropped into a context that did nothing to accompany it. No real reception project, no serious investment in cultural mediation, no mutual education. Only work, exploitation, and then emptiness.

In that emptiness, the ghetto was created. Not as a choice, but as a refuge.

And while politics pointed at the Bangladeshi as the cause of the problems, it carefully avoided talking about the economic choices that had produced them. About major industrial interests. About the fact that integration costs money, while building enemies generates consensus: when the wise man points at the moon, the fool looks at the finger.

From a distance, Europe can look like promise.

Up close, migrants often encounter suspicion.

Distance changes the story.

In between are people who are simply trying to live, send money home, avoid making mistakes. People moving within a system that does not truly want them, yet does not have the courage to say so.

This does not make Bangladeshis “the good ones” and Italians “the bad ones.”

That is a convenient simplification—the same one that fuels fear and conflict.

The point is another: as long as we are unable to look at migration as the consequence of structural choices, we will keep arguing about identity instead of responsibility.

And the price will always be paid by those with the least voice.

Ghetto Rhymes with Project

A ghetto does not arise by chance.

It is not a mistake. It is not a “cultural drift.” It is a project.

Not in the sense of a written plan, but as a coherent accumulation of omissions.

When, for years, you don’t invest in cultural mediation.

When you reduce reception to a public-order issue.

When you concentrate people in neighborhoods without services, without shared spaces, without real paths to integration.

When you ask people to work, but not to participate.

In Monfalcone this process is visible.

A large community, essential to the local economy, was left alone. No serious accompaniment, no mutual education, no political assumption of responsibility. Just work and silence. Then frictions emerge—surprise and indignation follow.

The ghetto then becomes the proof that “they don’t want to integrate.”

But this reading is inverted. The ghetto is often the only remaining space of protection for those who were never truly welcomed.

Meanwhile, pointing to an enemy works.

It simplifies. It compacts. Distracting is easier than explaining. Destroying is easier than building.

It is far more convenient to talk about culture, hygiene, religion, than to talk about industrial choices, precarity, exploitation, institutional responsibility.

The ghetto also serves this purpose: shifting the gaze from causes to consequences.

I am not absolving anyone.

Living in a society also implies adaptation, respect for rules, confrontation. Expecting integration without providing tools creates tension.

And tension, if unaddressed, hardens.

Politics rides this horse.

The ghetto is not the problem. It is the symptom.

And like all symptoms, it says far more about those who denounce it than about those who live inside it.

The First World of Relationships

We are used to classifying the world according to GDP, income, productivity.

First world, second world, third world. A scale that seems objective, but measures only one thing: money.

I began to wonder what would happen if we measured prosperity differently.

Not only in money, but in the density of bonds.

If we measured societies by the quality of relationships, by the ability to be together, to support one another in difficult moments, to recognize each other as part of a shared fabric, the first world might not be where we think it is.

There, relationships are more immediate, less mediated, less protected. Not because they are better in absolute terms, but because they are necessary. When survival is fragile, no one can really afford to live alone.

I used to tell them: “Okay… perhaps if you go to Europe you can make more money, but if you want to make friends, you better stay here”. They would look at me strange, silly.

We have built defenses, distances, emotional protocols. We have learned not to disturb, not to depend, not to ask for too much. In exchange, we have gained security—but lost something along the way.

I’m not idealizing. I’m not proposing models to import.

I know well that this kind of bond also has costs, limits, pressures. But ignoring what works elsewhere simply because it doesn’t fit our parameters is a form of blindness.

I started wondering whether the real divide was economic at all.

And perhaps true underdevelopment is not the lack of resources, but the inability to build bonds that hold when fear enters the scene.

Because in the end, wherever you were born, you don’t face the future alone.

Or at least, not without paying a very high price.

Leaving the Theater

The Elsewhere diaries, in their Bangladeshi chapter, end here.

Not because the conversation is exhausted, but because every experience, at some point, needs to be left to settle. Elsewhere was not an investigation, nor an exposé, nor a set of proposed solutions. It was a crossing. An attempt to stay inside complexity without reducing it to slogans, without choosing a side, without seeking consensus. These stories will soon meet those from Iraq, Turkey, and Germany from past years.

I have told what I saw and what unsettled me to question that intermediate space where certainties crack and questions become more honest.

I know not everything will be agreeable. I know some passages will remain uncomfortable. That’s normal. Complexity is not meant to reassure.

As with a film or a book, everyone takes away what they can, what they want—or nothing at all. There is no message to decode, no moral to applaud.

There is only an experience offered for what it was: partial, situated, incomplete.

Now it is time to leave the theater.

Not to forget, but to keep walking elsewhere, each with their own questions.

Elsewhere does not ask to be defended.

It asks only not to be simplified.

You can learn more about Elsewhere here: https://primipiani.net/elsewhere/

No Problem, I Love You – A selection of photos from Bangladesh: https://lyno-leum.com/portfolio/no-problem-i-love-you/

Many thanks to my precious and dearest collaborators Sharif, Meheki, Rahman, Ali, and Idris, and to all the families and new friends who welcomed me into their lives in Bangladesh.

Many thanks also to my dear friend and colleague Aurora, who supported me from Italy, and to Walton, who was at the very origin of this mission.